November 1, 2025

Leopold Museum Vienna: World’s Largest Egon Schiele Collection & Austrian Modernism

Architecture, Art, Culture, History

This page contains links through which we may earn a small commission should you decide to book a tour from our partner.

Top attractions:

About Leopold Museum

The Leopold Museum is Vienna’s definitive collection of Austrian modern art, housed in a striking white limestone cube within the MuseumsQuartier (7th district). Opened in 2001, it holds over 8,300 works assembled across five decades by ophthalmologist and collector Rudolf Leopold and his wife Elisabeth—a private passion that became a national institution.

The museum anchors its identity around two pillars: the world’s most comprehensive Egon Schiele collection (around 300 works including 48 paintings, numerous drawings, and archival materials) and the permanent exhibition “Vienna 1900. Birth of Modernism,” which traces Austrian art from the Secession through Expressionism. Key works include Klimt’s monumental “Death and Life” (1910/15), Richard Gerstl’s raw self-portraits, and Josef Hoffmann’s Wiener Werkstätte furnishings—all presented in light-flooded galleries designed by architects Laurids and Manfred Ortner.

Unlike Vienna’s imperial museums, the Leopold occupies purpose-built modern space. Panoramic windows on upper floors frame views of the Hofburg and city center, while the minimalist interiors let the art dominate. The building itself—a geometric counterpoint to the adjacent black MUMOK cube—has become a landmark of Vienna’s cultural quarter, visible from across Museumsplatz.

Secession style furniture. Photo by Alis Monte [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Connecting the Dots

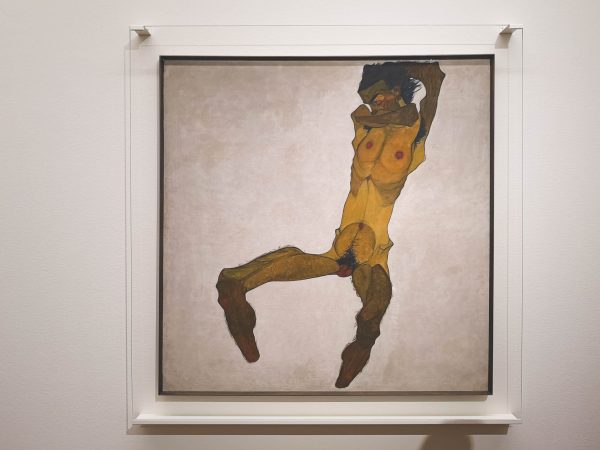

Egon Schiele, Seated Man Nude (Self-portrait), 1910. Photo by Alis Monte [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Connecting Vienna

Leopold Museum Details

- Location: Neubau (7th district), MuseumsQuartier

- Region: Vienna, Austria

- Address: Museumsplatz 1, 1070

- Entrance: Main Entrance (Museumsplatz)

- Opened: 2001 (21st century)

- Architectural Style: Contemporary / Modernist

- Entrance fee: €17 adults; €13 seniors; €10 students; free under 19

- Tickets: Available online and at the box office

- Opening hours: Wed–Mon 10:00–18:00; Closed Tue

- Phone: +43 1 525 70-0

- Transport: U2 MuseumsQuartier; U3 Volkstheater; Tram D, 1, 2, 46, 49, 71 (Dr.-Karl-Renner-Ring)

- Accessibility: Fully wheelchair accessible; lifts to all floors; accessible restrooms

Location

Current Exhibitions

- Vienna 1900. Birth of Modernism — exhibition spanning Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka, and the Wiener Werkstätte (Since 16 Mar 2019 – Permanent)

- Kowanz. Ortner. Schlegel (9 Oct 2025 – 11 Jan 2026)

- Hidden Modernism – The Fascination with the Occult around 1900 (4 Sept 2025 – 18 Jan 2026)

History & Development

Rudolf Leopold began collecting Austrian modern art in the 1950s—a time when Schiele and early Expressionists were unfashionable and undervalued. Working as an ophthalmologist, he and his wife Elisabeth amassed works systematically, often rescuing pieces from obscurity. By the 1990s their private collection had grown into the world’s most significant holdings of Schiele, Gerstl, and Vienna Secession decorative arts.

In 1994, facing the question of the collection’s future, the Leopolds negotiated with the Austrian state to establish the Leopold Museum Private Foundation. The Republic of Austria and the National Bank acquired the collection for approximately 160 million euros (collection valued around 570 million euros), keeping it intact and in Vienna. A purpose-built museum was commissioned as part of the newly planned MuseumsQuartier—a massive urban renewal project converting the former imperial stables into a contemporary cultural district.

Architects Laurids and Manfred Ortner designed the museum as a five-story white limestone cube, deliberately modernist yet proportioned to harmonize with the Baroque courtyard. Construction completed in 2001; the museum opened on 22 September with a mission to present Austrian modern art from 1880 to 1960 in depth. Rudolf Leopold remained active as honorary president until his death in 2010, continuing to refine the permanent displays and acquisition strategy. Today the museum operates as a public foundation, balancing its core collection with rotating exhibitions that place Austrian modernism in international dialogue.

Gustav Klimt, Death and Life, 1908-1915. Photo by Alis Monte [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Connecting the Dots

Egon Schiele, Stylized Flowers in Front of a Decorative Background, 1908. Photo by Alis Monte [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Connecting the Dots

Highlights

Egon Schiele Collection. The museum holds over 300 Schiele works—48 paintings and 180 drawings and watercolors—spanning his entire career from early experiments (1908) to the final months before his death in 1918. Key pieces include “Portrait of Wally” (1912), “Self-Seers II (Death and Man)” (1911), “The Embrace (Lovers II)” (1917), and dozens of radical figure studies that rewrote European figuration. No other institution offers this depth; you can trace Schiele’s evolution month by month.

Gustav Klimt, “Death and Life” (1910/15). Klimt’s monumental late masterpiece—a swirling allegorical composition contrasting Death (a skeletal figure in black and gold) with a tangle of sleeping humanity wrapped in ornamental robes. Originally shown in 1911 with a gold background, Klimt repainted it in deep blue after World War I, darkening the mood. At 178 × 198 cm / 70 × 78 inches, it dominates its gallery and rivals “The Kiss” in ambition.

Richard Gerstl. The museum holds the world’s largest Gerstl collection—critical for understanding Austrian Expressionism’s roots. Gerstl’s raw, psychologically intense portraits (including his 1908 self-portraits) predate and arguably surpass early Kokoschka and Schiele. He committed suicide at 25; the Leopold preserves nearly his entire surviving output.

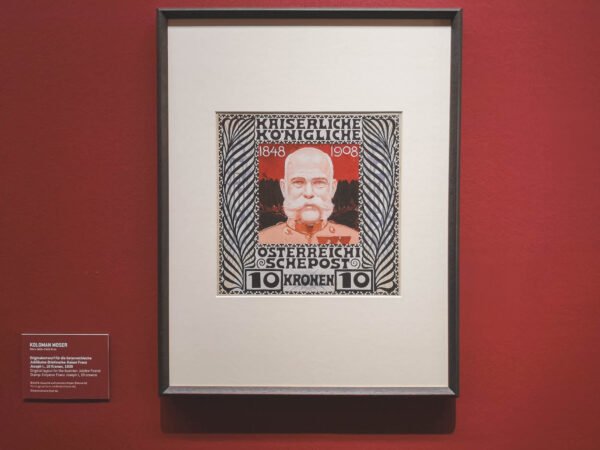

Wiener Werkstätte Rooms. Original furnishings, textiles, ceramics, and metalwork from Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, and their collaborators, displayed in period-inspired room settings. These objects demonstrate the Gesamtkunstwerk ideal—total design integration—that defined Vienna 1900 aesthetics beyond painting.

Albin Egger-Lienz. Monumental realist paintings of Tyrolean peasant life and World War I—Alpine social realism that parallels German Neue Sachlichkeit. The Leopold is the primary repository of Egger-Lienz’s work outside Tyrol.

Modernist furnishings. Photo by Alis Monte [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Connecting the Dots

Koloman Moser, Austrian Jubilee Postal Stamp: Emperor Franz Josef I, 1908. Photo by Alis Monte [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Connecting the Dots

Why Visit?

The Leopold offers what the Belvedere can’t: deep, sustained engagement with single artists across entire careers. Spend an hour with Schiele—trace his line from Academic nudes through angular distortion to the tender late portraits—and you’ll understand his project better than any monograph can explain. The collection’s density rewards repeat visits; regulars return for individual works, not overviews.

The architecture supports this intensity. Natural light floods the galleries through ceiling skylights and panoramic windows; walls are clean white; nothing competes with the art. Upper floors offer unexpected moments—turn from a Schiele self-portrait to face the Hofburg framed in glass, connecting the art to the city that produced and rejected it. The museum café becomes an informal salon where students sketch and argue theory.

Locals treat the Leopold as Vienna’s antidote to imperial grandeur. Where Schönbrunn and the Hofburg celebrate Habsburg power, the Leopold champions the artists who dismantled that world—Klimt’s eroticism, Schiele’s raw bodies, Gerstl’s psychological breakdowns, Hoffmann’s democratic design. The collection documents the avant-garde that emerged in imperial Vienna’s final decades and exploded after 1918. For first-time visitors, budget 2–3 hours: one hour for Schiele, 30 minutes for Klimt and Gerstl, the rest for the Wiener Werkstätte and temporary exhibitions. Combine with MUMOK next door for a full morning of modernism, or pair it with the Kunsthistorisches Museum across Museumsplatz to see what the revolutionaries were revolting against.

Gustav Kilmt’s “Death and Life” in Leopold Museum. Photo by Alis Monte [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Connecting the Dots

Women’s modernist clothing by Gustav Klimt. Photo by Alis Monte [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Connecting the Dots

All content and photos by Alis Monte, unless stated differently. If you want to collaborate, contact me on info@ctdots.eu Photo by Alis Monte [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Connecting the Dots

Ticket Discounts

Visit the Leopold Museum for less with Vienna’s top city passes. The Vienna Pass gives free access to the Leopold Museum and 70+ attractions citywide, plus skip-the-line entry. For flexible transport and discounted tickets to major sights, get the Vienna City Card (24h–72h) with unlimited public transport and museum savings. Both passes include free cancellation up to 24h before activation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where is the Leopold Museum?

In Vienna's 7th district (Neubau), at Museumsplatz 1 within the MuseumsQuartier, directly behind the Kunsthistorisches Museum.

When was it opened?

The museum opened on 22 September 2001, after the collection was acquired by the Austrian state in 1994.

What are the opening hours?

Wednesday–Monday 10:00–18:00; closed Tuesday (as of October 2025). Closed 24 December.

What should I not miss?

Egon Schiele's "Portrait of Wally" and "The Embrace," Klimt's "Death and Life," Richard Gerstl's self-portraits, and the Wiener Werkstätte rooms.

Is it accessible?

Yes—fully wheelchair accessible with lifts to all five floors, accessible restrooms, and wheelchairs available at the entrance.

How long do I need?

Allow 2–3 hours for highlights; 3–4 hours to explore the full permanent collection and temporary exhibitions.

Which public transport is best?

U2 to MuseumsQuartier (direct access); or U3 to Volkstheater (5-minute walk); or tram 1, 2, D, 71 to Burgring.

Can I buy tickets online?

Yes—available on the official website and via partners; recommended to skip lines during peak times (weekends 11:00–15:00).